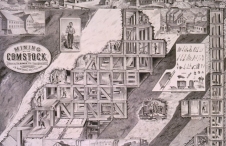

Archaeology on the Comstock

Professional archaeology has yielded many insights into Comstock life over a century ago. The discovery of an African American saloon, the world's oldest Tabasco Sauce bottle, and the first examples of human DNA retrieved from artifacts other than human remains have captured international headlines. Still, the real story involves the patient, labor-intensive analysis of hundreds of thousands of artifacts examined in context.

At least half the buildings in Virginia City during the 1870s are now gone. Most left archaeological traces. For decades, this resource attracted bottle diggers who eliminated thousands of sites searching for a few collectibles. Early attempts to professionally excavate Comstock resources yielded some results. Unfortunately, the discipline tended to shun publicity, and the benefits of careful archaeology remained largely unknown.

In 1993, the State Historic Preservation Office, the University of Nevada, Reno, and the Comstock Historic District Commission cooperated with dozens of dedicated volunteers to begin a systematic examination of Virginia City's archaeology. The team has excavated four saloons, a boarding house, the site of the 1877 Piper's Opera House, part of Chinatown, and numerous house sites. Other coalitions of archaeologists and volunteers have added to the story, most notably in 2004 with the examination of the remains of a Silver City schoolhouse.

One of the problems with professional archaeology is that when placed in competition with bottle diggers, the latter will always cover far more ground. The archaeologist's slow methodology is exacerbated in the lab where cleaning, cataloguing, and analyzing artifacts takes three to five hours for every hour in the field. A bottle digger can destroy many sites in the time an archaeologist takes to understand a single location.

Since 1993, professionals have opened sites to visitors and the media, sharing knowledge, displaying artifacts, and telling their story using every possible outlet. This has inspired some residents to oppose bottle digging, as they come to understand that their archaeology is like a library of books, each in danger of being destroyed by those who would tear out pages for personal benefit.

One of the most important Comstock contributions to historical archaeology is its examination of saloons, the most comprehensive in the West. Shanahan and O'Callaghan's Hibernia Brewery and Saloon, O'Brien and Costello's Shooting Gallery and Saloon, John Piper's Old Corner Bar, and William Brown's Boston Saloon are each understood in ways not possible with the limited written record. More importantly, it is possible to compare the artifacts in each, concluding, for example, that the Hibernia had the poorest cuts of meat and the African-American-owned Boston had the best. Piper provided a refined environment for a modest price, tackling the problem of poor water quality in the early 1860s with a carbon water filter imported from London. The discovery of the world's oldest Tabasco Sauce bottle at the Boston Saloon adds another layer to the story, demonstrating an interest in exotic cuisine while placing the product in the West long before historians thought possible.

A hypodermic needle recovered from beneath a house's floorboards yielded another sort of insight, this time at a location other than a saloon. The wide needle of the implement required the patient to open a vein for irrigation, resulting in fatty cells being left behind inside the tool. Analysis of retrieved DNA demonstrated that at least four people of both genders used the needle. The method was echoed at the Boston Saloon site where archaeologists retrieved DNA from inside a pipe stem, revealing that a woman once smoked it.

These are only a few examples of how dedicated professionals have changed our perception of the early mining community. Comstock archaeologists are rewriting history one site at a time, bringing the past to life.

Article Locations

Related Articles

Further Reading

None at this time.