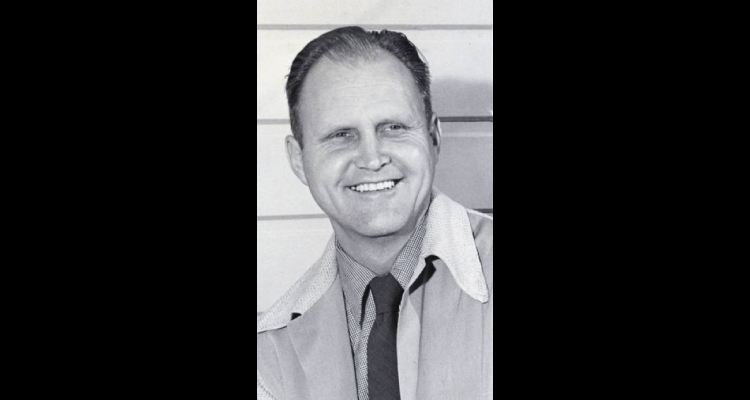

Cliff Segerblom

Cliff Segerblom divided his creative energies between photography and painting. In 1938, he accepted a position with the Bureau of Reclamation and became the first official photographer of the Boulder Canyon Project. His pictures were featured in Life, Time, National Geographic, and one of his photographs is in the Museum of Modern Art collection in New York. Segerblom excelled in watercolor, and his studies of Nevada towns and terrain were often shown in exhibitions across the state. He was a recipient of a Nevada Governor's Art Award in 1984. Segerblom died in 1990.

Below is reprinted with permission from the Nevada Historical Society Quarterly.

Nevada Historical Society Quarterly

Volume 33, Summer 1990, Volume 2

Dennis McBride

CLIFF SEGERBLOM (1915-1990)

If there were such a thing as an artist laureate, Cliff Segerblom is one who could claim that title in Nevada. For more than fifty years, with his photography and painting, Segerblom has quietly chronicled the American Southwest, and particularly Nevada's vanished frontier, its mining and farm towns, its rivers, canyons, deserts, and mountains. As much as any other Nevada artist, Segerblom will be noted for preserving much of Nevada's visual history, for in many cases Cliff's paintings are all we have to remind us of what Nevada used to be like in off-the-track places like Tungo, Jarbidge, Cherry Creek, Goldfield, or Belmont.

Originally from California, Segerblom attended the University of Nevada in 1934 on a football scholarship, but majored in art. He married Nevada native Gene Wines, and when they came to Boulder City in 1938 to visit Gene's relatives, the Bureau of Reclamation offered Cliff a job as photographer for the recently completed Hoover Dam Project. Segerblom was the bureau's first official public-relations photographer, and many of his shots of the Boulder Canyon Project have appeared in such national publications as Life, Time, and National Geographic. His photograph of Hoover Dam's needle valves in operation is in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

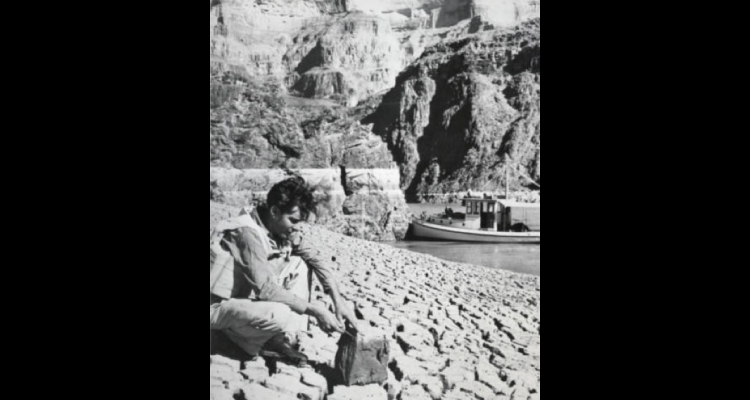

When he wasn't photographing Hoover Dam, Segerblom was loaned by the Bureau of Reclamation for other government projects. While on assignment in 1939 for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Segerblom documented the Havasupai Indian tribe in their Grand Canyon home. After he and Gene were married in 1941, they moved to Panama, where he photographed the Third Locks Project on the Panama Canal. Occasionally, they took trips to Guatemala where Segerblom painted street scenes.

But the glory of his government assignments came in 1969 with an invitation from the secretary of the navy to record the splashdown of Apollo 12. Segerblom's acrylic painting of that historic event is now part of the navy's official art collection.

Segerblom made his reputation in a variety of media, although his watercolors are the most characteristic. He paints in acrylics as well, and he's developed a couple of unique styles. Sometimes Segerblom will paint over a watercolor with acrylic, then hose it down. The tempera underneath dissolves and peels, and produces a striking effect of weathered wood and peeling paint which is perfect for his architectural paintings.

And about ten years ago Cliff began painting landscapes in what he calls his venetian-blind technique. These acrylics are painted one strip at a time across the canvas, which produces a highly stylized, refracted effect.

Cliff has not only an artist's eye for composition, balance, and color, but a storyteller's intuition for the revealing detail, which he uses in making unobtrusive comment about his subjects.

Political Circus, for instance, an acrylic painted in 1986, depicts the weathered wall of a building papered over with tattered campaign posters. We recognize the names: Bryan, Sawyer, Del Papa, Laxalt, Santini. What's revealing of Segerblom's sense of humor in this work is that the building is an abandoned gas station, and pasted to the trunk of a nearby tree is a poster advertising a circus clown.

The same kind of detail adds narrative depth to Last Picture Show, Caliente. The last film screened at Caliente's Rex Theatre, closed in 1976, was When Legends Die; the letters hang askew on the ruined marquee, and two cowboys stand together in the box-office shadows.

There is irony in Big Mac, which pictures the stripped-down wreck of a truck in an overgrown barnyard, and Downtown, where the sleek, contemporary skyline of Las Vegas rises behind a bleak line of Union Pacific boxcars.

Segerblom enjoys a little mystery, too. In Blue Monday, Carson City, he's painted one of his favorite subjects: Victorian architecture, in this case an elaborate window frame reflecting the blue light of early morning. Peering between the curtains inside, nearly invisible, is a face of androgynous character.

What the public does not often see of Segerblom's work, unfortunately, are his unusual portraits, to which he brings the same transcending quality that softens his inhospitable deserts and canyons. Seen in public only briefly before it was sold, Patriarch is an Eastern European orthodox Jew who looms in one side of the painting, supported by a cane. The same technique Segerblom has used to create the look of weathered wood in his buildings here produces in the patriarch's face a weathered and desperate character. And since the patriarch is the only figure on the canvas, his troubled expression is inescapable.

Cliff Segerblom has brought prestige to the Nevada art scene with his national and international awards, citations, and commissions, including the Governor's Arts Award which he received in 1984. It was a fifty-year retrospective of his work in 1987, sponsored by the Nevada State Museum and Historical Society, which proved not only its great artistic merit but its social and historic value as well.

Article Locations

Related Articles

None at this time.

Further Reading

None at this time.