Gilbert Natches

Gilbert Natches was a Native American artist whose panoramic oil paintings of the Pyramid Lake region were realized with a limited palette and uncomplicated compositions. A nephew of Sarah Winnemucca, Natches gained recognition in 1914 by editing Northern Paiute texts for the noted anthropologist, Arthur Kroeber, at the University of California in Berkeley.

Below is reprinted with permission from the Nevada Historical Society Quarterly.

Nevada Historical Society Quarterly

Volume 33, Summer 1990, Number 2

Peter L. Bandurraga

GILBERT NATCHES

Gilbert Natches1 was a painter of Nevada landscapes, especially scenes of Pyramid Lake, in the years between 1910 and 1940. Many of his paintings show the dwellings and lifeways of his Paiute relatives and neighbors on the Nixon Reservation. A grandson of Chief Winnemucca and a nephew of Sarah Winnemucca Hopkins, Natches grew up in a world irredeemably changed by the white man. Throughout his life, he explained and illustrated the ways of his people, for the curious whites and especially for the Paiute children, so that they might know how life had been before.

As is often the case with native Americans born in the nineteenth century, precise data on Natches are sketchy at best. The 1910 census indicates he was then twenty-seven years old, born in 1883 in Nevada of parents also born in Nevada. On the other hand, both the obituary that appeared in the Lovelock Review Miner on June 4, 1942, and Orner C. Stewart writing in 1941 give Natches's age as fifty-four, which places his year of birth around 1887. Stewart, who used him as an informant in his research, states that Natches was born at Brown's Station, southwest of Lovelock, but lived for thirty-six years at Nixon, returning to Lovelock in 1936.2

Stewart and several other writers mention that Natches suffered a crippling accident as a child, falling off either a train or a horse. As a result he spent a good deal of time at home listening to his mother and grandmother talk about the old days, before the white intrusion. Although Natches did not have firsthand knowledge of Paiute ways, Stewart was impressed "by his breadth of knowledge and by his ability to express himself. His lack of personal experience with aboriginal culture limited his knowledge; notwithstanding, he surpassed anyone else I found at Lovelock."3

In 1914 A. L. Kroeber, the anthropologist from the University of California who was excavating the archaeological finds at Lovelock Cave, invited Natches to visit the university museum in San Francisco and assist him in editing Northern Paiute texts earlier collected by W. L. Marsden. Although differences in dialect made the original project unfeasible, Natches stayed in California for several months, learning to write the Paiute language phonetically and leaving behind a Paiute verb list, a series of phrases, and some stories and songs that Kroeber later edited and had published in a volume of American Archaeology and Ethnology.4 It is interesting that these stories and songs relate by and large to the Ghost Dance religious revival that had been so influential among the Paiutes of northern Nevada during the 1890s.

While a resident at the Affiliated Colleges of the University of California in San Francisco, which is where the university museum was then located, Natches apparently gave an interview to a reporter. A long article about him appeared in the Sunday supplement of the San Francisco Chronicle for October 25, 1914, and contains the most detailed description of the artist's life and work to be found. The unnamed journalist made much of Natches's distinguished Paiute lineage and, in the paternalistic fashion of the day, paid effusive tribute to his various accomplishments: learning to speak English although his school attendance spanned only six months; drawing and painting in watercolors, oils, and sepia; and playing the violin. Indeed, Natches apparently made a living playing for dances in Reno. The author provides a vivid description of Natches's introduction to painting:

He has always associated with the whites and early in life adopted their dress and manner of life. At his father's death he was left with a farm of many acres, which he conducted successfully until the big idea–the idea to paint and become an artist–came to him. Then he rented his farm and turned to art for a living. He kept a couple of horses and a wagon and day after day used to drive over the Nevada desert with his painting outfit, which was given him by a Mr. Severance, a minister at Reno. Gilbert's favorite spots seem to have been Blue Lake and Pyramid Lake, in Washoe County. Here he was in a sort of basin surrounded by mountains, bare and dun colored, whose serrated edges seemed to touch the sky. Almost at the foot of the mountains nestled a turquoise-blue lake, aptly named Blue Lake; the sky, too, was blue with a few fleecy clouds on the horizon; the pungent odor of sagebrush was in the air. The soul of the Indian was thrilled with the beauty, the witchery of it all. He dismounted from the wagon, set up his easel and began to paint. When the picture was finished he took it back to Reno where it commanded instant attention. He received orders to paint more and spent more and more time on the desert alone with nature. His pictures sold from $5 to $10 apiece.5

However romanticized this Sunday supplement account may be, the bare bones at least are likely true. In fact, Kroeber arranged an exhibition of Natches's paintings at the Affiliated Colleges while he was in residence. The Carson City News of October 13, 1914, reported on the show and included the following comment: "The paintings are all of picturesque scenes in the vicinity of the artist's home near Wadsworth, and show the buttes and mesas, the salt lake with its steep islands and the distant ranges of the desert in varying lights and seasons."6 The author of the Chronicle article pointed out that Natches occasionally put on the headdress of his illustrious grandfather Winnemucca, which was a part of the university museum's collection. The piece is illustrated with a photograph of Natches wearing the feathered bonnet while seated at an easel, with Ishi looking on. Ishi, of course, was the last of the Yahi of California; he had been rescued from annihilation a few years earlier and was also a resident at the university museum.

Natches continued to paint his desert world for more than two decades. A short article in the Nevada State Journal in March of 1925 announced that one of his paintings would be included in the upcoming Transcontinental Highway Exposition.7 As late as 1941, in the "Arts and Artists" column of the Reno Evening Gazette, Lillian Borghi noted that a number of Natches's landscapes were included in an exhibition arranged by the Parent-Teacher's Association of Lovelock.8

By 1941, however, Natches had long been in failing health and circumstance. A series of letters from 1929 to 1937 in the John T. Reid Collection at the Nevada Historical Society documents the rather desperate straits the artist found himself in, as his eyesight failed and the Bureau of Indian Affairs from time to time cut off his government allowance. The latter consisted of $10 per month in groceries doled out at the reservation store, with which Natches supported his mother, his sister, and himself. Reid, the geologist and amateur archaeologist who was closely involved in the excavations at Lovelock, acted as a good friend to Natches and wrote several letters to officials at the Bureau of Indian Affairs. He also called on the influence of Senators Tasker Oddie, Key Pittman, and Patrick McCarran to bring relief to the artist. Natches wrote to Reid many times, asking him to secure a copy of Life Among the Paiutes, an account written by his aunt Sarah Winnemucca, and for help in having a copy made of a medal that had been presented to his father, Chief Natches, by Humboldt County in recognition of his aid in the Bannock Paiute War in 1878. In addition, Reid in 1929 tried to track down a photograph of Natches's father that the artist had sent to Seattle for copying. Apparently, either the company or its sales representative was fraudulent, and the photograph does not seem to have been returned. Reid also helped the artist have other photographs of family members copied, and he twice secured new prosthetic devices to help Natches get around on his crippled leg.9

In what little documentation there is of Natches's life, there are few references to the nature and quality of his art. He painted landscapes of the terrain where he was born and lived his life. They had mountains, lakes, and sky and occasionally aboriginal Paiute dwellings. Natches lived in a "civilized" house on the reservation, according to the 1910 census, so it is likely he was documenting the old ways in his paintings, just as he had helped Kroeber document the Paiute language in 1914.

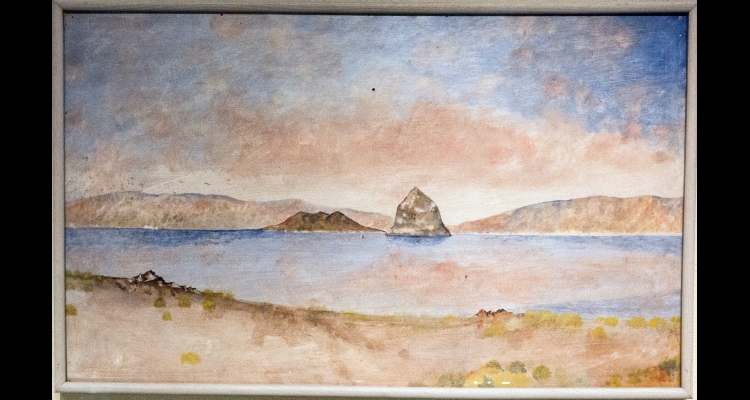

Four of Natches' s paintings came into the possession of the Nevada Historical Society with the purchase of John T. Reid's papers and other materials in 1948. They are all labeled in the handwriting of the society's then director, Jeanne Elizabeth Wier: "Pyramid Lake, painted by Gilbert Natchez." Two are on canvas, and two on poster board. One has the figure $10 penciled on the back, and another is signed "Gilbert Natches" and has $26 and 1925 written on the back. Two are simply landscapes, one of Pyramid Lake with Anaho Island and the other of the Sierra. The other two have wickiups and brush sun shades, with a few people moving around, unposed. The people are too distant to have distinct features and appear to be mainly women and children engaged in daily activities.10

In none of the paintings has Natches used a particularly strong palette. The colors are all muted, tending to greys, browns, and pale greens. Even when he portrays a sunset and the clouds are brushed with rose and peach, the color is still somewhat dim. The sky, which the Chronicle writer noted so vividly, is usually rather grey and pale, as if the desert is covered by high clouds and the air is a bit thick. One more point strikes the viewer when seeing the four paintings together: The dwellings and the mountains are always in a horizontal line across the middle. There is, with one exception, a long, rather empty foreground and a lot of sky, either with prominent clouds or simply empty. The mountains, true to all of Nevada, are always present and are the predominant character in the compositions. The human presence is anonymous and almost negligible. Although the wickiups are rendered in sharp detail, there is little precise drawing elsewhere. Natches's brush strokes are boldly evident, and he applied liberal amounts of paint. But most details are only suggested. The large forms of mountains, clouds, and lake are what stand out. The over-all effect is pleasant and peaceful, putting the viewer into the land, but not too close to the major features.

Natches painted what he knew, the land around him. He lived a hard life, apparently with little complaint. He obviously loved his heritage and tried to do something to preserve knowledge of it.

NOTES:

1. Two spellings of the artist's name, Natches and Natchez, appear in various references. He signed his Paiute name in his correspondence Natches.

2. United States Decennial Census, 1910, Nevada, Washoe County, 270; "Gilbert Natchez Dies at Stewart Indian Hospital," Lovelock Review Miner, 4 June 1942, 1:3; Omer C. Stewart, Culture Element Distributions: XIV, Northern Paiute, Anthropological Records, Vol. 4, no. 3 (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1941), 363.

3. Stewart, loc cit.; Lovelock Review Miner, 4 June 1942, loc cit.

4. Gilbert Natches, "Northern Paiute Verbs," American Archaeology and Ethnology, University of California Publications, Vol. XX, A.L. Kroeber, ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1923), 24559. Some of Natches's stories and songs also appear in Notes on Northern Paiute Ethnography: Kroeber and Marsden Records, Robert F. Heizer and Thomas R. Hester, with the assistance of Michael P. Nichols, eds. (Berkeley: Archaeological Research Facility, Department of Anthropology, University of California, 1972).

5. "Scion of Indian Aristocracy Paints for University Professors," San Francisco Chronicle, 25 October 1914. It is likely that "Blue Lake" is the now dry lake in Kumiva Vallev, between Pyramid Lake and Lovelock.

6. "Indian Artist Winning Fame on the Coast," Carson City News, 4 October 1814, 3: 3.

7. "Painting of Pyramid Lake, Done by Paiute Indian, To Be Shown," Nevada State Journal, 29 March 1925.

8. Lillian Borghi, "Arts and Artists," Reno Evening Gazette, 29 November 1941.

9. Gilbert Natches File, John T. Reid Papers, Nevada Historical Society.

10. The four paintings have temporary accession numbers 1988.1-4. There are no other accession records beyond the correspondence concerning the transfer of Reid's estate to the Historical Society. That correspondence notes only "four Indian pastels." The Eighteenth Biennial Report of the Nevada Historical Society (Carson City: Nevada State Printing Office, 1948) 16, 19, records the purchase. These paintings were displayed for a number of years at the legislative building in Carson City.

Article Locations

Related Articles

Further Reading

None at this time.