Goldfield

The last gold rush in the West began with a discovery around 1900 by the great Shoshone prospector Tom Fisherman. Two young Tonopah roustabouts, Harry Stimler and William Marsh, followed him to the site and staked claims in late 1902. They continued to work these claims sporadically over the ensuing months, occasionally joined by other prospectors. A brief stampede in May, 1903 to the spot they called Grandpa quickly subsided, but in October, thirty-six enthusiasts gathered to organize the mining district and rename it Goldfield. Not until Alva Myers succeeded in getting a sufficient stake from investors to demonstrate the value of the Combination Mine did the new district really take off. Ore shipments began in late 1903.

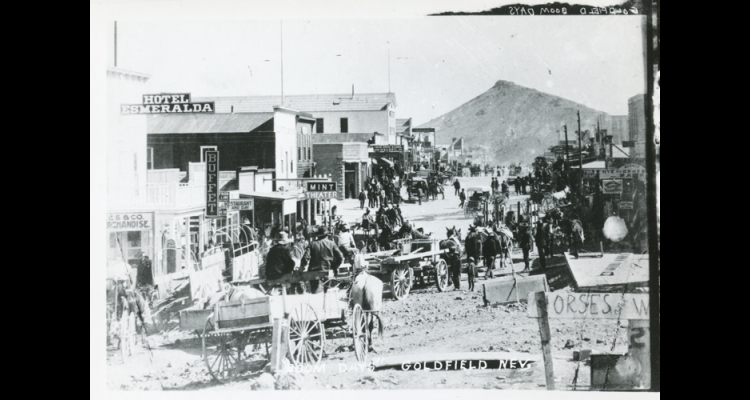

In those days, Goldfield consisted of a mere handful of tents. Inside four years, however, it had burgeoned into the largest city in Nevada, with 18,000 to 20,000 people. The gold rush peaked in 1906, when the discovery of the Hayes-Monnette bonanza in the Mohawk Mine ignited such excitement that boomers stampeded into town, the market in Goldfield mining stocks skyrocketed, customers packed the saloons like bees in a hive, and the streets were so crowded that a man could only move at a slow shuffle. Goldfield played a vital part in reversing the long depression that had depopulated Nevada for twenty years since the decline of the Comstock.

During these glory days, Goldfielders enjoyed a variety of amusements. Sports, such as the Gans-Nelson lightweight boxing championship, drew huge crowds. They could dine in fine restaurants serving such delicacies as quail on toast, and afterward take in a twentieth century innovation—a movie. Circuses and traveling theatrical companies came to town. Pianos tinkled in the dance halls, and those in search of riskier entertainment could head up to the drug emporiums in "Hop Fiends' Gulch." Although the town had an elegant men's organization, the Montezuma Club, as well as the Pirates of Cruiser line and other social clubs, the saloons remained both primary amusements and highly profitable businesses, the forerunners of today's casinos. Goldfielders celebrated every holiday with exuberance, culminating in the Fourth of July, 1907, with a parade, a variety of races, a drilling contest for miners, and an "All Fools Carnival" and cakewalk, for which women dressed as men, men as women, and both as animals, including a swan and a giraffe.

Yet these exciting times had a dark underside. Waves of influenza and pneumonia (known as the "black plague") swept the city from 1904 through 1907, taking a heavy toll. During the worst month, November 1906, pneumonia caused eighty percent of the deaths in Goldfield. The numbers of homicides and suicides exceeded the national norm. Goldfield's women contributed more than their share to the roster of the dead, and died tragically younger than other American women. Accidents in the mines also claimed lives, embittering the miners who believed the safe timbering that might have saved them cost the owners more than their deaths: "Again a worker's life has been sacrificed to the God of greed," they declared.

More fortunate in transportation than many earlier camps, Goldfield was served by three railroads connecting to three major trunk lines. The most important, the Tonopah and Goldfield, arrived in 1905. Other forms of transportation showed the transitional nature of the times. Motorcycles zipped around the plodding burros in the street. Auto stages replaced the mud wagon stages of earlier days, and a law officer thundered after a speeding auto—on his horse.

The last great gold rush was already slackening by late 1907. The organization of the Goldfield Consolidated Mines Company, including most of the productive mines, by ex-gambler George Wingfield and U.S. Senator George Nixon, was turning Goldfield into a company town inhospitable to fortune hunters with high hopes. The radical miners' unions—the combined Western Federation of Miners and the Industrial Workers of the World—had been smashed in a drive led by Wingfield under the aegis of federal troops. To justify the army presence, the self-defense shooting of restaurateur John Silva by union organizer Morrie Preston had served as a useful propaganda tool. The overheated market in mining stocks had crashed. The decline in Goldfield mining stocks averaged sixty-five percent or more. Transactions shriveled. It is estimated that losses to investors far exceeded the value of mining production.

Despite the brevity of the boom, Goldfield had a substantial impact on Nevada politics. The influx of Democratic voters to Goldfield and the other new mining camps produced a lasting political realignment in 1908. Two dissident political movements that burst out of Goldfield enlivened politics to a degree that has not been seen since. The Republican Progressives, led by George Springmeyer (this author's father) and "Lighthorse Harry" Morehouse, tried to turn their party in the direction of reform but were defeated by the old Southern Pacific railroad machine; the Socialists elected several local and state officials and saw some of the reform issues they had championed co-opted by the major parties.

Yet, badly hurt by the destruction of the radical unions, they too failed at the polls. The victors were a new elite from the central Nevada mining boom that replaced the old political elite centered on the Comstock, and for years the bipartisan political machine headed by Wingfield dominated state politics. Indeed, Goldfield's influence extended beyond politics because it assured the triumph of mining camp ideology over other value systems. That meant unfettered individualism over community and the primacy of materialism over moral values.

After the bonanza spirit faded, Goldfield rapidly declined. Although the mines still produced well, the population dived to 5,400 in 1910 and continued to shrink. Worse lay ahead: The Goldfield Consolidated Mill closed in 1919; then a fire that started in a bootlegger's still in 1923 left much of the city a blackened, smoking rubble. Goldfield's mining production through 1960 has been calculated at around $90 million, considerably less than other early twentieth century mineral discoveries at Tonopah and Ely, but neither of these could match Goldfield in its glory days for excitement and great expectations.

Still the Esmeralda county seat, Goldfield survives today, with a scanty population and a few buildings, such as the large brick Goldfield Hotel and the old jail, remaining from the boom days.

Article Locations

Related Articles

Further Reading

None at this time.