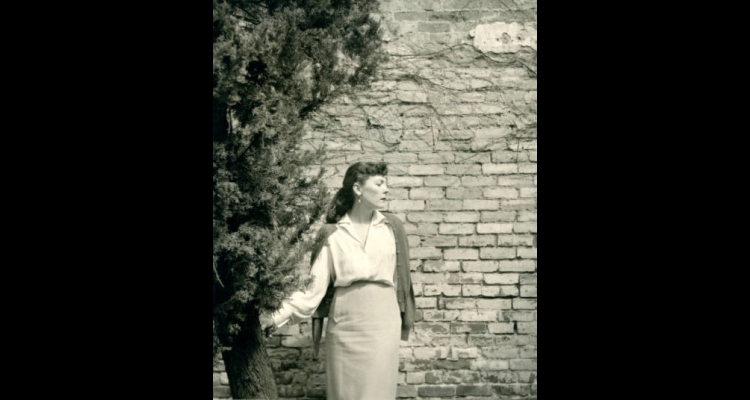

Joanne de Longchamps

One can hardly return to Nevada letters of mid-century without reading Joanne de Longchamps (1923-1983). A student of two art forms, poetry and collage, she spent a lifetime piecing into them her love of Greece, animals, and the struggle between Eros and Thanatos—love and death. In her art were the dreams of those particulars, and she drew for the reader their multiple outlines. At times, her fascination with these themes became what sustained her, particularly late in life when she had so many health problems.

The daughter-in-law of the well-known Reno architect, Frederick (Fredric) DeLongchamps, she married his adopted son Galen, and they had a son, Dare. She later changed the spelling of her last name to "de Longchamps." She found numerous colleagues with whom she began to carve out her niche in Northern Nevada. She studied with Walter Clark, painted with Joan Arrizabalaga, and formed the Reno Poetry Workshop with Harold Witt, Irene Bruce, and Thelma "Brownie" Ireland. Clark was a careful reader of de Longchamps' prose and her poetry, although the prose was never published. Her editors at Illinois University Press were equally discerning. They published her third book, The Hungry Lions, in 1963. Her predecessors in that series would go on to affect the course of modern poetry for several decades: Kizer, Wagoner, Aiken, Miles, Roethke, and Lorca in translation.

The desert informed de Longchamps' work—she thought of Pyramid Lake as having the light of the Aegean—and indeed, this landscape is like Greece. She must have felt a spiritual connection with Greek mythology that she could not express without art: the infinite human, the persistent drama of love, man, and beast. Eventually, she would incorporate Nevada into that myth.

In the late 1970s, William L. Fox produced the first of two small press books that wove de Longchamps' collage and poetry together. These books are marvels of aesthetic and visual quality. They manage to blur the line between print and image and make the object of her art, whether salamander or eel, an object to behold. She spent hours researching each poem and collage, tearing paper from magazines—never using scissors—to assemble the near-perfect image on the page. Then she returned to the science that grounded her poems in fact: "The larvae of eels are named elvers. The currents they ride are called eelfares."

In time, de Longchamps became central to the arts community in Northern Nevada. She worked with painters Jim McCormick, Robert Cole Caples, Richard Guy Walton, and Zoray Andrus; English professors Ahmed Essa, Robert Hume, and Charlton Laird; novelist Robert Laxalt, and dozens more who painted or wrote. But in the end, her life was one of severe anguish: Dare had taken his life, Galen left, and her health failed. She never accounted for these losses except by way of art. Her long poem to her deceased son is something no mother should have to write, but it is like no other poem from a mother to a son.

De Longchamps might have died wondering if her art mattered. Too ill to leave her home, and too tired to create, she held a last exhibition of her collages at the Sheppard Fine Arts Gallery at the University of Nevada, Reno in the fall of 1983. This was her swan song, her elegy to the art that was her vessel, her namesake, and her creator.

Article Locations

Related Articles

None at this time.

Further Reading

None at this time.