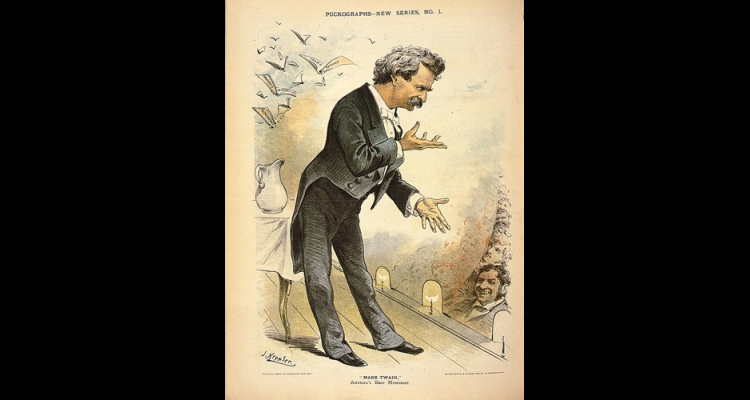

Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens was born in 1835 in Florida, Missouri, and raised there in the eastern part of the state. His schooling was minimal; he was essentially self-taught. As a teenager, he worked for local newspapers, and then for printing shops in Cincinnati and other eastern cities. In 1857, now twenty-one, Sam persuaded Horace Bixby, a Mississippi River steamboat pilot, to accept him as an apprentice. Sam sailed up and down the Mississippi first as an apprentice, then as a full-fledged pilot until the advent of the Civil War, when hostilities closed the river to civilian traffic. Clemens fled the oncoming holocaust by attaching himself as a secretary to his brother Orion, who had just been appointed Secretary of the Nevada Territory and was leaving for Carson City on July 21, 1861.

Soon tiring of working for his brother, Sam was attracted to the prospect of becoming rich by prospecting for gold and silver. The work turned out to be unexpectedly arduous and unprofitable, as did another job in a stamping mill. While he toiled at these physical jobs during the day, Sam took to writing humorous sketches at night, and sent them to the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise. A particularly clever satire caught the eye of Joe Goodman, the newspaper's editor. Goodman offered him a job as a reporter, and Sam accepted with alacrity. His literary career had begun.

The Enterprise was already the outstanding newspaper of the Comstock Lode, and on its way to becoming one of the best in the country. It attracted the best writing talent in the area by offering high wages and unusual freedom of discretion. Besides its owners, Joe Goodman and Denis McCarthy, both unusually self-possessed young men of integrity, ability, and ambition, the Enterprise also employed William Wright, the best writer on the Comstock, who used the penname of Dan De Quille. Other employees included the combative editorialist Rollin Daggett, the printer Steve Gillis, and a number of other transient but talented Sagebrush journalists. Sam and De Quille became roommates, and under De Quille's experienced but gentle tutelage and Goodman's inspiration, Sam quickly absorbed what De Quille had to teach him and soon revealed himself as the possessor of original genius. He adopted the penname of Mark Twain and within months was producing works of humor that rivaled De Quille's.

In 1864, Twain moved to California, worked for such papers as San Francisco's Call and the Alta California, and the Sacramento Union, while continuing to send contributions to the Territorial Enterprise. Twain's years in Nevada and California ultimately became the basis for the main group of chapters of Roughing It (1872). In 1866, The Sacramento Union engaged him to write a series of travel letters from Hawaii, which became the latter chapters of Roughing It.

In 1867 the Alta California in return for another series of travel letters paid Twain's fare on the steamship Quaker City, which left New York in June with a group of well-to-do tourists for a 164-day excursion to the Azore Islands and an itinerary of visits to ports on the Mediterranean and Black Seas. Twain was part of a small band of passengers on that voyage who scorned the wealthy and sanctimonious culture of the majority. His satirical account of the trip became The Innocents Abroad (1869). The book was a success and from then on Twain's reputation as an author steadily grew.

Twain's early career was eventful. In 1870, he married Olivia Langdon of Elmira, New York, and started family life in Buffalo, New York, where he was part-owner of a newspaper. In 1871, he sold his house and share in the newspaper and moved to Hartford, Connecticut, a prestigious cultural center. All the while, Twain was a prolific writer and promoted himself by collecting his short works and publishing them as books. His first book, for example, was The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County and Other Sketches (1869). Among the highlights of his early career, in addition to those already mentioned, were The Gilded Age (1874) and, especially, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876). Although most of his books were regarded as humorous, recent scholarship has established a dark side to his writing, an ambivalent and deeper level of continuous engagement with serious ideas that is concealed by the sugar-coating of surface humor.

In 1883, his middle period under way, Twain wrote Life on the Mississippi, a memorable account of his associations with that mighty river, and in 1884-85 (in British and American editions), he published The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, his most famous work. Among other books, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court came out in 1889, and Pudd'nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins in 1894.

Twain's last period, the latter 1890s and the first decade of the twentieth century, is characterized by works that show with increasing obviousness his disillusion with life and God: Following the Equator (1897), the Mysterious Stranger manuscripts (1897-1908), and Letters from the Earth (1909), and short stories and essays of social, political, and theological criticism.

At the time of his death in 1910, Twain was easily America's most beloved author. Since then, his reputation has increased by becoming not only America's most respected author, but also one of world literature's giants. Scholarship has discovered depths and shadows in his writing where before had only been noticed a bright and cheery surface. Famous studies of his literature pointed out the biographical importance of two periods of his life: the Matter of Hannibal and the Matter of the River. To this has recently been added the Matter of the West, which demonstrates that the years Twain spent in Nevada and California were formative ones for his thought and art. Now that much Sagebrush literature is being recovered, it is possible to recognize Twain's assimilation of distinctive Sagebrush attitudes and techniques, most especially that of the hoax. He came to incorporate hoaxes into most of his major literature for he found them to be perfect covers for his dark and ironic philosophy. His literature thus combines a genius for humor with profound despair.

Article Locations

Related Articles

None at this time.