Mormons and Genoa

What some consider Nevada's first Euro-American town appeared in the Carson Valley in 1850. Gold Rush fever had swept the nation, sending fortune-seekers streaming into California. The Humboldt Trail, one route west, crossed Northern Nevada and deposited prospectors at the foothills of the Sierra Nevada. At this point a handful of Mormons established a trading post to provision road-weary travelers. Their success and the Comstock Lode's discovery soon attracted others, but Genoa and Dayton now competed for the title of the first American settlement in the western Great Basin.

In July 1847, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints President Brigham Young arrived in the Salt Lake Valley and declared, "This is the place." The Mormon's isolation soon ended with the Mexican-American War—which added the present-day Southwest to the United States—and the throngs heading westward for the California Gold Rush.

In the spring of 1850, a group of Mormon men headed for California's gold fields. They traveled the Humboldt Trail across what is now Northern Nevada and ended up in Carson Valley. Before crossing the Sierra Nevada, a few decided they could make more money provisioning road-weary miners. Joseph DeMont, Abner Blackburn, and Hampton S. Beatie set up a trading post. Their venture was profitable, but they returned to the Salt Lake Valley as winter approached.

By 1851, miners were wandering back from California's overworked gold fields searching for the next big strike. Having found gold on the western side of the Sierra Nevada, several dozen decided to try their luck in the eastern foothills, in what was then Utah Territory. Reacting to this influx of miners into the region, Mormon John Reese arrived to establish a new trading post. Reese brought along some settlers and re-claimed the DeMont, Blackburn, and Beatie site, naming it Mormon Station.

The settlement was almost 500 miles from Salt Lake City, inspiring the group to form a squatter's government to provide civil and legal services. But the Mormons were not alone as others also responded to the region's economic opportunities and established local businesses. Animosities grew until the non-Mormons (gentiles) petitioned California's government for oversight in a reaction against Salt Lake City's distant domination that they viewed as theocratic, designed to combine church and state.

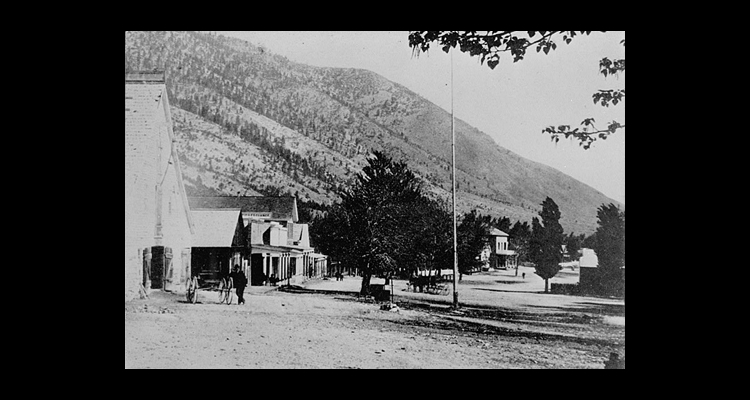

To maintain control over the region, Utah's territorial legislature organized Carson County in January 1853, and in 1854 Brigham Young appointed associate Orson Hyde as the Carson County administrator. Hyde organized the government and encouraged Mormons and gentiles to peacefully coexist. He changed the name Mormon Station to Genoa, conducted a boundary survey, and planned for elections.

Nevertheless, in 1856 when sixty new Mormon families arrived, gentile resistance to Salt Lake City's supervision increased. By the end of the year Hyde had grown so frustrated with the worsening conditions that Utah's leadership summoned him home. In 1857, afraid the U.S. Army was poised to invade his fortified homeland, Brigham Young recalled all outlying Saints. A few families stayed in the Carson Valley, but most left. As they moved out, non-Mormons seized their property, bringing to an end Mormon control over the settlement.

Article Locations

Related Articles

None at this time.