Nineteenth-Century Immigration and Ethnicity in Nevada: An Overview

Throughout the nineteenth century, immigration dominated Nevada, affecting its development and society. Nevada had more foreign-born per capita than any other state in 1870 and the percentage of Nevada's immigrants rivaled that of other states for much of its early existence. In spite of the importance of foreigners to Nevada, it is difficult to generalize about how immigration and ethnicity affected people's lives. Every group was different, and each person unique. In addition, the ethnic profile of Nevada has changed constantly since the 1850s when new arrivals began to settle the region.

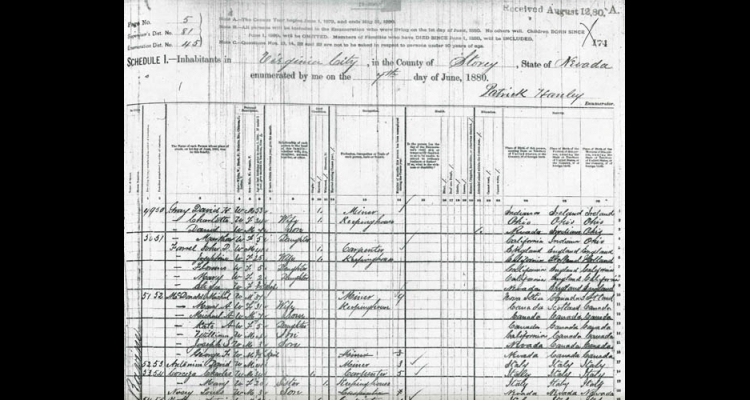

Census records including the federal effort every ten years, the Nevada territorial census in the early 1860s, and the state census of 1875 yield results vital to the study of immigration and ethnicity. Fortunately, information from the federal manuscript census pages covering Nevada from 1860 to 1920 is online in the form of a fully searchable database at nvshpo.org, the only one of its kind in the nation. This tool offers an understanding of the state's population.

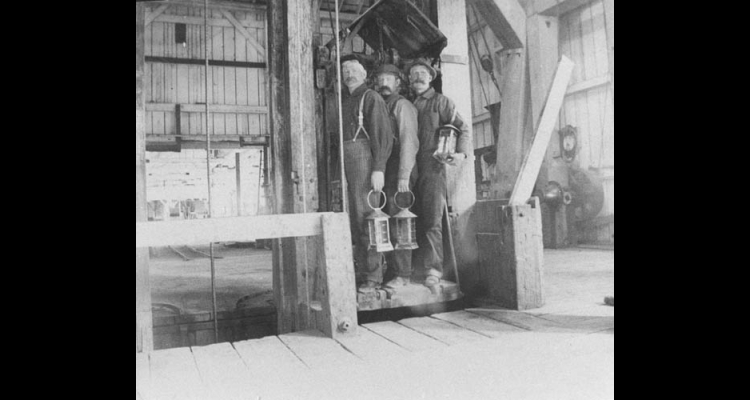

During the 1860s and 70s, the fabulous wealth of the Comstock mines combined with discoveries in Austin, Hamilton, Eureka, and elsewhere to attract people from throughout the world. While every inhabited continent had representatives in Nevada, most countries sent only a few. It excites the imagination to mention immigrants from places like Morocco, Slovenia, Java, Iceland, and Arabia, but people from remote places such as these were rare. Most of Nevada's nineteenth-century population came from several countries in North America, Western Europe, and China.

The majority of people living in Nevada originated from the United States and its territories. Proximity and the promise of opportunity also attracted Canadians and speakers of Spanish. The United Kingdom, which through the turn of the century included Ireland, sent most of the Europeans. Germans, Italians, the French, and Scandinavians were also well represented. Those who came from Eastern Europe were often Yiddish-speaking Jews having more in common with German immigrants than with the Slavs of their homelands. It is worthwhile to note that four immigrant groups who settled in Nevada were uniquely western. The Cornish, the Chinese and other Asians, the speakers of Spanish, and the Basques arrived predominately in the West, each for their own reasons.

While it is easy to focus on the new arrivals who helped build a young state, it is crucial to remember that Northern and Southern Paiutes, Washoe, and Shoshone Indians provided the ethnic bedrock of Nevada. Settlement devastated the indigenous populations. Still, Great Basin American Indians were resilient. They adapted and found ways to thrive as they confronted a radically changed environment.

When it comes to questions of gender, age, occupations, and the willingness to linger in the state, each immigrant group assumed a different profile, but there were always people who defied the stereotype of their cohort. Still, some generalizations are possible. Among immigrants, the Irish, Chinese, English (including the Cornish), Canadians, Germans, and Italians were numerically the most important during the nineteenth century, although the standing of each relative to the others could change from year to year. Cornish immigrants tended to leave Nevada as soon as the mining industry faded in the 1880s. Many single Irish men did the same, but Irish women and their families were more likely to stay. Italians also tended to linger as did the Basque, who arrived late. Both the Italians and the Basques were inclined to return to Europe, sometimes remaining, but often coming back again to Nevada.

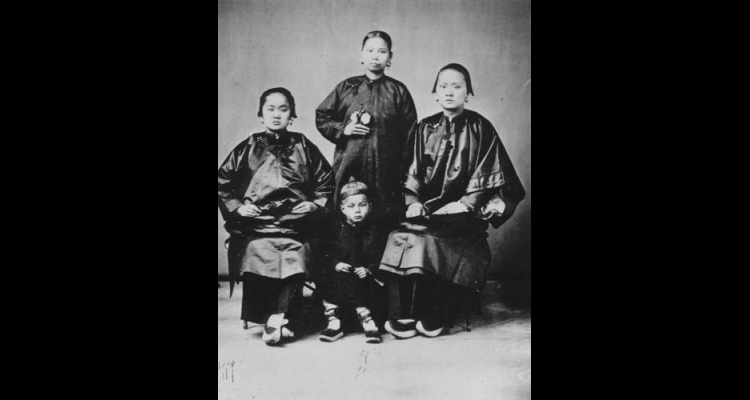

Immigration historians have often looked at the Chinese as sojourners, itinerant workers who intended to return to Asia, but the Chinese were not unique. Many people from throughout the world, including the eastern United States, hoped to go back home once they made their fortunes in Nevada. Few were, in fact, as tenacious as the Chinese, but eventually most left.

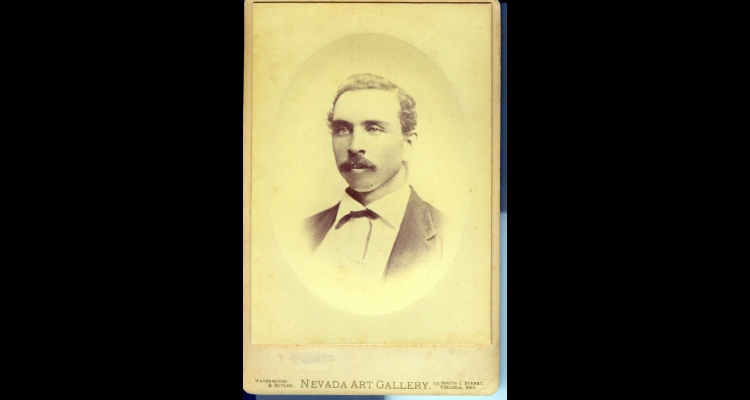

Prejudices among the dominate North Americans and Western Europeans in Nevada were sometimes different from those found in other states. The Irish, who fought so hard for a better place on the ethnic ladder in the eastern U.S., arrived in large numbers just as Nevada society took shape. They refused the position of second-class citizens. Protestants may have scorned Catholics, but they were unable to impose a lower status on the Irish. Similarly, prejudice against African Americans was not as keenly felt in nineteenth-century Nevada as it was elsewhere. Although African Americans certainly endured racist oppression, they were too few to attract as much venom as others did, and at least for a while, the effect of the Civil War often promoted good will towards the victims of slavery.

The Chinese, on the other hand, received the greatest burden of racist bile from Europeans and Americans in the state during the nineteenth century. Federal law denied citizenship to the Chinese and restricted the immigration of Chinese women. State law limited marriage between Chinese and other groups. In addition, primary sources document day-to-day acts of cruelty inflicted on the Chinese. Nevertheless, these immigrants arrived by the thousands, worked hard, and helped build the state from its very beginning.

Because of the diversity in Nevada, many communities enjoyed a calendar rich with ethnic celebrations. From the Scottish Robert Burns suppers and Highland games to the celebrations of independence for the various Spanish-speaking countries, from the Irish St. Patrick's Day to Northern Paiute autumn gatherings, from Chinese New Year to the Jewish holy days, mining camps and other Nevada communities took pleasure in an international spectrum of humanity.

With the decline of the mining industry in the 1880s, Nevada's ethnic population transformed. Many left the state and fewer newcomers arrived. An increasing number of Nevadans were second generation, "hyphenated" Americans who focused more or less on the birthplaces of their parents. Turn-of-the-century discoveries of ore deposits resulted in a new rush to Nevada, and this influx included thousands of foreigners, setting the stage for a new period of ethnic diversity.

Article Locations

Related Articles

None at this time.