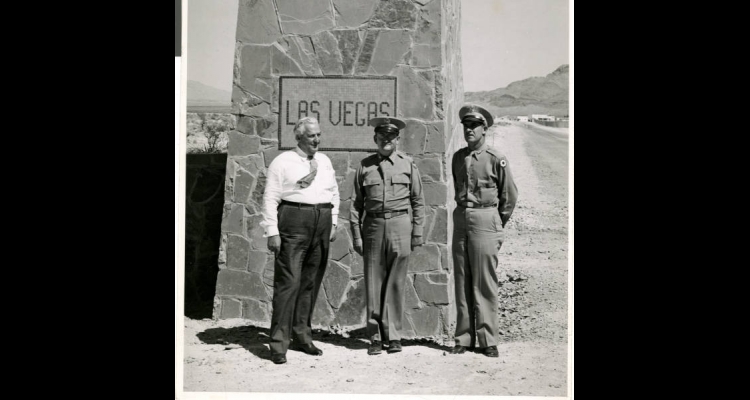

Patrick Anthony McCarran

Patrick Anthony McCarran was a notable United States senator who was active in Nevada's political life for over a half century. He was born in Reno on August 8, 1876, the son of Irish immigrants. When he was two, his parents moved to a sheep ranch bordering the Truckee River some fourteen miles east of Reno. Because of the ranch's isolation he was unable to start his schooling until the age of ten when he could ride horseback to school. He was always four years older than anyone else in his class.

McCarran began attending the University of Nevada in Reno in 1897, but dropped out in his final semester. He read in the law, and in 1905, he was admitted to the Nevada bar. His first case was successfully defending his own father, a fiery old man, for cutting down telephone poles on the family property. In 1903, he married Martha Harriet Weeks, and they subsequently had five children.

McCarran spent the next thirty years of his life practicing law and participating in politics. His specialty was criminal law, which he practiced in Reno, and briefly in Tonopah. With a reputation as an effective attorney, McCarran became known as the man to call for help. Always willing to extend himself for a client, he defended accused murderers, ladies of the night, an abortionist—twice, perhaps unusual for a practicing Roman Catholic layman—and accused bank robbers. McCarran was an exceptionally formidable courtroom antagonist, a Clarence Darrow type in many ways. He could be flamboyantly oratorical or coldly logical, depending on the occasion. His heart was usually with "the sinner," and he was a great attorney for the defense. McCarran was also a skilled divorce lawyer, representing most prominently film star Mary Pickford in 1920.

His political career seemed, up to 1932, far less successful. During the thirty-year period from 1902 to 1932, McCarran ran for eight political offices, winning only three of the races and losing five. Twice he was prevented from running at all. The highest office McCarran attained in this period was justice of the Nevada Supreme Court, which he held from 1913 through 1918. He was defeated in his bid for reelection, an unusual circumstance for a Supreme Court justice. Above all McCarran wanted to be a United States senator, and a concerted effort was made to keep him out of that position. Up until 1932, he was deemed a political failure.

Nevada's political leaders prevented McCarran's ascendancy for so long and so systematically, in part, because of his personality—he was viewed as bullheaded and uncooperative. In addition, he had run afoul of political boss George Wingfield and his friends. McCarran and Wingfield shared a mutual dislike of one another. Much of this personal resentment may have occurred because McCarran represented Wingfield's common-law wife, Mae, in her bitter divorce action against Wingfield in 1906. As defense attorney in the 1927 Cole-Malley case, McCarran put Wingfield on the stand and publicly tried to humiliate him. Among the Wingfield group which dominated Nevada politics, McCarran also had a reputation for being a Democratic Party maverick who conformed to no rules other than his own.

In 1932, when McCarran made yet another run for the U.S. Senate, he received the Democratic nomination by default since everyone believed he would lose to the popular but lackluster incumbent Republican senator, Tasker Oddie. This was, however, during the Great American Depression and the conventional wisdom failed to take into account that the influx of workers to construct Hoover Dam had changed the politics of the state. Besides, the Wingfield banks had closed one week before election day. McCarran was elected by a narrow vote.

Pat McCarran was re-elected as United States Senator three times: in 1938, 1944, and 1950. His active stand on national and international issues had little to do with this success. More than almost any other senator, he was supported by the voters because he was interested in taking care of the needs of his constituents. When McCarran was elected senator there were roughly ninety thousand people in the state, about the size of a typical Chicago aldermanic ward. When he died it had ballooned up to perhaps 200,000. When McCarran campaigned, he could speak to people personally—he knew many of his constituents by their first name. His Washington, D.C. office, operating under the extremely efficient leadership of Eva Adams, served the interests of Nevadans, and letters and requests from his constituents received immediate attention.

McCarran also reaped political rewards from the fact that Nevada had no law school at this time. For twenty-two years, he put students from his home state through law school in the District of Columbia. He also gave them jobs in his office, or on his committee—and he had a lot of jobs to give—or in the U.S. capitol building. Known as "McCarran's boys," these young men often returned to Nevada where they developed political careers of their own. They became vital cogs in McCarran's machine.

In return for his many favors, he demanded loyalty. McCarran was a man who knew his enemies and did not forgive their sins. Political opponents (especially those in his own Democratic party) were to be defeated and crushed. He was behind the casino advertising boycott of Hank Greenspun's Las Vegas Sun in 1952, a tactic especially designed to destroy that paper because of its courageous opposition to him. But the very abrasiveness of his personality and tactics created antagonism. In his re-election fights, he invariably had primary opposition, most famously in a bruising battle with Vail Pittman in 1944. By the early 1950s McCarran's power seemed to be on the wane in Nevada.

In truth, his state was outgrowing him. Las Vegas was rapidly developing in the last years of his life, and he could not understand the growth, nor could he understand the newcomers to the area. This great influx of arrivals into the state inspired a new environment that seems to have made McCarran particularly uncomfortable. Nevada's rapid growth contributed to problems and issues that he would not have recognized. He considered the gambling industry as something to be manipulated for his political ends, rather than something to be regulated and reformed by the state. He was completely indifferent to civil rights issues, and to the problems occasioned by the rise of Las Vegas, a burgeoning community important to him only if it suited his political interests.

McCarran died of a heart attack on September 28, 1954, immediately after addressing a political rally in Hawthorne. His reputation has suffered in the years since his death, because he represented the values of an older generation of leadership, and was blind to the direction which his state was to take. Thus his contribution to the future development of Nevada turned out to be far less than what had seemed to be likely at the time.

Article Locations

Related Articles

None at this time.